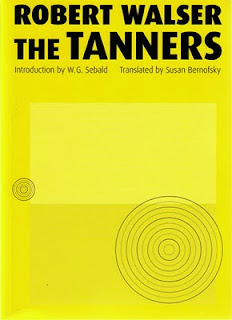

I think I first heard about Robert Walser through an interview in the early nineties with the Brothers Quay, who went on to film Walser's novel Jakob von Gunten. About the same time I bought The Walk and other Stories, with its introduction by Susan Sontag, in Camden's much-missed Compendium Bookshop. After enjoying the Quay Brothers' film Institute Benjamenta (1995) at the ICA (which may soon be going the way of Compendium), I taped it when it came on TV and remember showing it to one or two people, none of whom seemed as impressed as I was. I thought that both Walser and the Quays would remain a minority taste, but now we seem to be in the midst of what one review calls a miniature Walser renaissance. New translations are appearing and I have just finished reading Susan Bernofsky's translation of The Tanners (you can read an excerpt at The Brooklyn Rail). I'm once again going round trying to tell people how great Walser is - it would be a marvellous book anyway but it also happens to have a cool cover design and Sebald essay for an introduction.

Google The Tanners and you'll find plenty of reviews, so I won't say much here about the novel itself. My excuse for mentioning it at all is Kaspar Tanner, a landscape painter, brother of the book's main character Simon. The quote above comes from a passage where Simon is looking at his brother's pictures. He goes on to say: "It cuts so deeply into us when we, lying at a window, dreamily watch the setting sun; but that's nothing at all compared to a street when it's raining and the women are daintily raising their skirts, or to the sight of a garden or lake beneath the weightless morning sky or to a simple fir tree in winter or to a boat ride at night, or a view of the Alps." These images made me think of haiku, and a few sentences further on Simon refers to his sister's friend, a poet thus: "people are saying he's built himself a hut up in the high pastures so he can worship nature undisturbed, like a Japanese hermit." Sadly we don't get to see this hut (if indeed it exists) in the novel.

Susan Sontag wrote that Walser's stories and sketches reminded her of 'the free, first person forms that abound in classical Japanese literature.' The story that most impressed me in that first Walser anthology I read was 'Kleist in Thun' (1913), about the great German writer who took his own life in 1811. In it, Walser (to quote W. G. Sebald) 'talks of the torment of someone despairing of himself and his craft, and of the intoxicating beauty of the surrounding landscape.' 'Time and again I have immersed myself in the few pages of this story' wrote Sebald, in the essay 'Le Promineur Solitaire: A Remembrance of Robert Walser' which appears as the introduction to The Tanners. He quotes Walser's description of the lake and the Alps dipping 'with fabulous gesture their foreheads into the water.' At another point in the story Walser pictures Kleist on a skiff, looking out at the clear morning lake. 'The mountains are the artifice of a clever scene painter, or look like it; it is as if the whole region were an album, the mountains drawn on a blank page by an adroit dilettante for the lady who owns the album...' (trans. Christopher Middleton).

Thun c. 1900 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

No comments:

Post a Comment