Having mentioned in my last post one enjoyable book published last year, I'd like to take this opportunity to recommend another, Christopher de Hamel's much-praised Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts. Plants, birds and animals abound in medieval manuscripts, as is evident in the cover of the book itself, an illustration from the Morgan Beatus, fifth of the twelve Remarkable Manuscripts that the author visits. Morgan is the Morgan Library in New York, Beatus is Beatus of Liébana (c. 730 – c. 800), a monk whose commentaries on the Apocalypse were written in the Picos de Europa mountains just at the time Charlemagne was fighting the Moors in Spain. The manuscript was made later, in north-west Spain, and is actually signed by a scribe called Maius (d. 968). It includes a map ('extremely naive and based on echoes of Roman geography') and Mozarabic paintings with colours and patterns suggesting 'the tiles and mosaics of Islamic architecture', but nothing, unsurprisingly, that could be called a 'landscape'. Later in the book, though, there is a full-page landscape illustration and it appears in what is probably the most famous of de Hamel's Remarkable Manuscripts.

Illustration from the Carmina Burana

Source: Wikimedia Commons

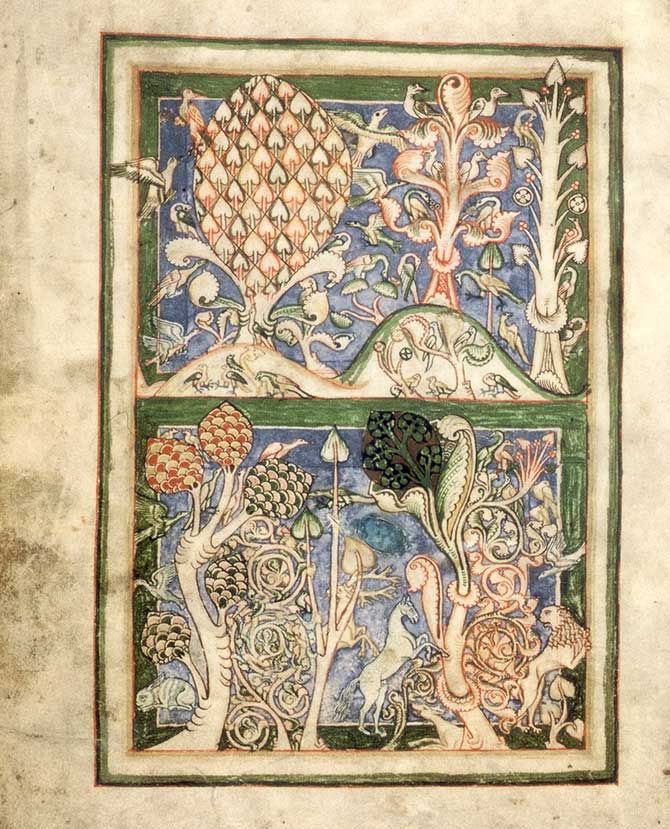

The Carmina Burana is a collection of songs and poems, mainly about love and drinking, made around 1230 somewhere in the county of Tyrol, in what is now Austria. It has become world famous thanks to Carl Orff's cantata, first staged in 1937; his setting of the first song in the manuscript, O Fortuna, has been recycled endlessly in films and will forever be associated in Britain with the advert for Old Spice aftershave. Here though I am interested in one of the other poems, which begins "Ab estatis floribus amor nos salutat' ('From the flowers of summer, love greets us...') The accompanying illustration, de Hamel writes, 'shows two scenes in verdant woodland. This must be a prime candidate for the earliest pure landscape in all of medieval art.'

As you can see, this woodland in the Carmina Burana is not exactly realistic. It is not the German forest that will appear, three hundred years later, in the first independent landscapes painted by artists like Altdorfer and Huber. Nor is it remotely like the detailed scenes that appear in the margins of high-quality fifteenth century illuminated manuscripts, and which resemble those wonderful views seen through windows in contemporary Northern Renaissance portraits. This illustration was conceived at a time when no landscapes as such were being painted in the West. Now, as I insert a reference to the Carmina Burana into my international landscape and culture chronology, I can't help wondering what its illuminator would have made of a Southern Song Dynasty scroll painting...

Clearly the scene depicted in this manuscript is not even a naive attempt at topography. As de Hamel points out, 'the inclusion here of a lion is much more appropriate for the Garden of Eden than for a familiar spring day in the German woods.' Those strange, luxuriant trees look primeval. In the top section we see birds which, according to Genesis, appeared on the fifth day of Creation, and in the bottom half are the animals that arrived a day later. This is not then the setting for a bawdy German love song. It is a medieval vision of the original landscape, created by God.

As you can see, this woodland in the Carmina Burana is not exactly realistic. It is not the German forest that will appear, three hundred years later, in the first independent landscapes painted by artists like Altdorfer and Huber. Nor is it remotely like the detailed scenes that appear in the margins of high-quality fifteenth century illuminated manuscripts, and which resemble those wonderful views seen through windows in contemporary Northern Renaissance portraits. This illustration was conceived at a time when no landscapes as such were being painted in the West. Now, as I insert a reference to the Carmina Burana into my international landscape and culture chronology, I can't help wondering what its illuminator would have made of a Southern Song Dynasty scroll painting...

Clearly the scene depicted in this manuscript is not even a naive attempt at topography. As de Hamel points out, 'the inclusion here of a lion is much more appropriate for the Garden of Eden than for a familiar spring day in the German woods.' Those strange, luxuriant trees look primeval. In the top section we see birds which, according to Genesis, appeared on the fifth day of Creation, and in the bottom half are the animals that arrived a day later. This is not then the setting for a bawdy German love song. It is a medieval vision of the original landscape, created by God.

No comments:

Post a Comment